Steel buildings are often selected because of their predictability. When properly engineered, they offer clear pricing, defined schedules, and long-term performance certainty. When engineering is incomplete, incorrect, or poorly coordinated, that predictability disappears quickly. Costs rise, timelines stretch, and responsibility becomes blurred.

Engineering errors typically increase steel building costs through redesigns, foundation rework, erection disruptions, and long-term performance limitations. Many of these issues stem from incomplete steel building engineering that fails to coordinate loads, connections, foundations, and erection sequencing as a unified structural system.

In Canada, steel building projects are shaped as much by permitting, inspections, and climate conditions as by construction speed itself. Engineering decisions made early in the project lifecycle often determine whether a building proceeds smoothly or becomes a series of expensive corrections.

Who This Article Is For

This article is intended for building owners, developers, and project managers planning permanent steel buildings in Canada where schedule certainty, inspections, and long-term performance matter. It may not apply to temporary storage structures or lightly engineered enclosures where full code compliance is not required.

What Counts as an Engineering Error in Steel Buildings

Engineering errors do not always mean incorrect calculations or unsafe structures. In many cases, the building technically meets minimum code requirements but fails to reflect real-world conditions, future use, or site-specific constraints.

Common engineering errors include:

- Incomplete or optimistic load assumptions

- Poor coordination between steel and foundation design

- Under-scoped connection and bracing design

- Erection-stage stability not fully analyzed

- Serviceability limits not aligned with actual use

- Generic assumptions applied across different sites

In Canada, where snow, wind, and frost conditions vary significantly by region, engineering assumptions that work in one location can create cost issues in another. These structural demands are governed nationally by the National Building Code of Canada, which defines load criteria for snow, wind, seismic forces, and safety performance across regions.

Why Engineering Errors Are So Costly in Steel Construction

Steel buildings rely on precise load paths. Unlike some construction systems that can tolerate field adjustments, steel structures expose design inaccuracies quickly.

When an engineering assumption is incorrect, cost impacts typically appear in one or more of the following ways:

- Redesign after permitting begins

- Structural modification during erection

- Long-term operational or maintenance limitations

Each outcome increases cost far beyond the engineering effort that would have prevented it.

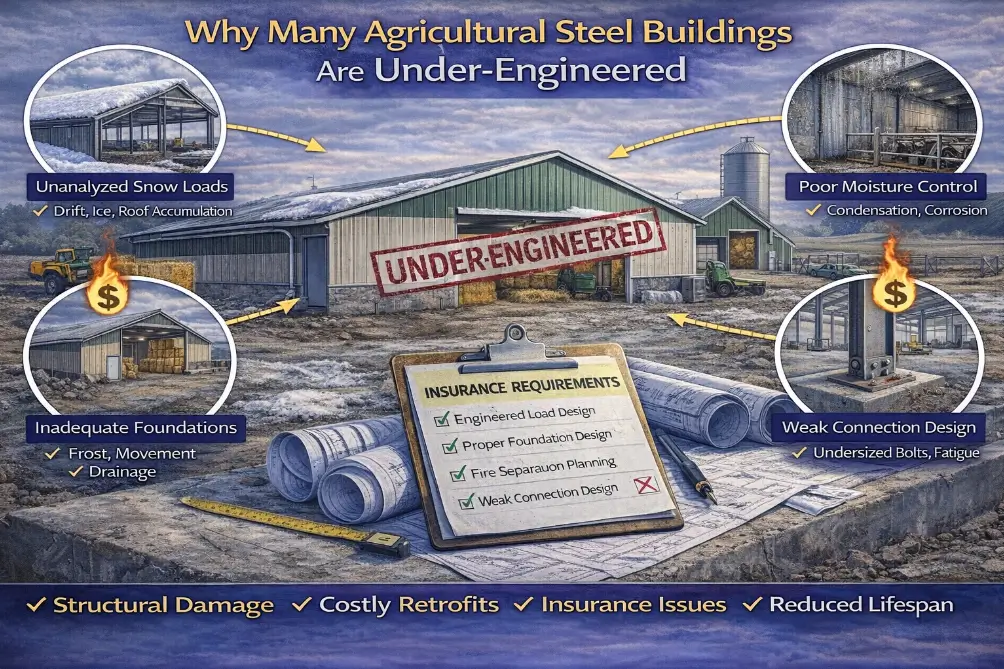

Incomplete Load Analysis Is the Most Common Problem

One of the most frequent engineering errors involves incomplete load analysis.

Examples include:

- Underestimating snow drift and accumulation zones

- Simplifying wind exposure classifications

- Ignoring future equipment or mezzanine loads

- Overlooking crane or hoist requirements

- Assuming generic occupancy instead of actual use

In Canada, snow, wind, seismic forces, and service loads vary not only by province but by site exposure and building geometry. When these factors are not fully analyzed, redesign often occurs after permit review or inspection feedback.

Redesign at that stage almost always increases cost.

Foundation Coordination Errors Multiply Costs Quickly

Foundation coordination is where engineering errors become most expensive.

Common issues include:

- Anchor bolt layouts not matching steel drawings

- Column reactions exceeding footing capacity

- Frost protection assumptions not validated

- Slab loads underestimated or misallocated

When foundation drawings and steel drawings are not coordinated early, corrections frequently occur after concrete placement. At that point, costs escalate through demolition, rework, schedule delays, and inspection resets.

Steel buildings tolerate very little error at their base. Small foundation inaccuracies often force significant structural adjustments above. This is why proper foundation design for steel buildings must be engineered alongside frame reactions, frost conditions, and site-specific soil behaviour.

Connection Design Is Often Underestimated

Connections are where loads transfer between structural members. They are also one of the most commonly under-scoped elements in steel building projects.

Engineering errors related to connections include:

- Designing primary members without full connection detailing

- Assuming standard bolted connections without validation

- Omitting erection-stage forces

- Underestimating fatigue or movement effects

When connection design is incomplete, fabricators or erectors are forced to resolve issues in the field. Field solutions cost more than shop-designed connections and introduce schedule and safety risk.

Erection Engineering Is Frequently Overlooked

Many steel building designs focus only on the completed structure and overlook erection-stage stability.

Engineering errors during erection planning can result in:

- Temporary bracing failures

- Unsafe erection sequencing

- Crane coordination conflicts

- Stop-work orders from safety authorities

In Canada, erection safety is regulated and enforced. Structures must be stable not only when complete, but at every stage of assembly. Engineering that ignores erection loads shifts risk to contractors and owners and often results in delays and additional cost. Many of these delays arise from overlooked temporary bracing requirements during steel building erection that are essential for stability and regulatory compliance.

Serviceability Errors Affect Long-Term Performance

Not all engineering errors appear during construction. Some emerge slowly during operation.

Serviceability-related errors include:

- Excessive roof deflection

- Door and opening misalignment

- Cladding movement

- Vibration under equipment loads

A building can meet minimum code requirements and still be poorly engineered for its actual use, resulting in avoidable cost and operational issues.

Correcting serviceability problems after construction is far more expensive than addressing them during design.

Early Signs of Engineering Risk in Steel Building Projects

Owners can often identify engineering risk early if they know what to look for.

Common warning signs include:

- Quotes issued before engineering scope is defined

- Foundation drawings prepared without steel reactions

- Erection sequencing not shown on structural documents

- Generic load assumptions applied across different sites

- Limited clarification of who is responsible for coordination

These signals do not guarantee problems, but they increase the likelihood of downstream cost exposure.

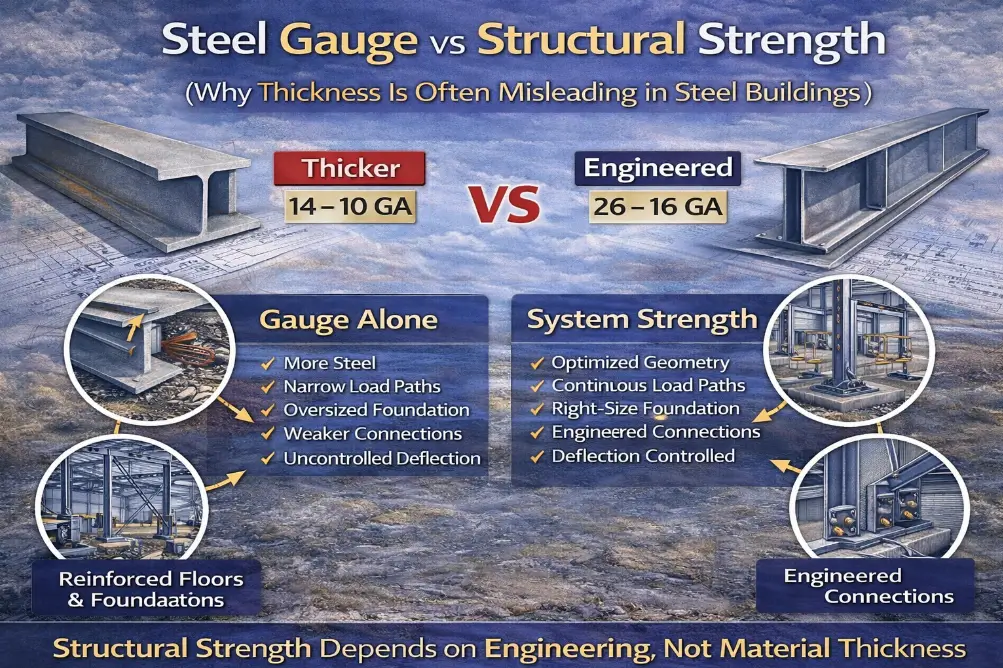

Under-Engineering vs Over-Engineering

Engineering errors occur at both extremes.

Under-engineering increases cost through redesigns, delays, and corrections. Over-engineering increases cost through unnecessary material use and fabrication complexity.

Both outcomes reduce project efficiency.

The objective is not minimum engineering or maximum engineering. The objective is accurate engineering aligned with actual project requirements.

How Engineering Errors Trigger Change Orders

Many change orders trace back to early engineering assumptions that were never fully validated.

Common triggers include:

- Permit reviewers requesting additional calculations

- Inspectors identifying discrepancies between drawings

- Owners requesting features not structurally accounted for

- Contractors encountering unbuildable details

Each change order increases direct cost and indirect cost through delays, administration, and coordination time. These revisions commonly connect back to design changes that affect steel building pricing once early engineering assumptions are corrected or expanded.

The Hidden Cost of Engineering Revisions

Engineering revisions rarely affect only one component. A small change can cascade through:

- Structural members

- Connections and bracing

- Foundations

- Fabrication schedules

- Erection sequencing

In steel construction, revisions are rarely isolated. Early accuracy matters.

Who Ultimately Pays for Engineering Errors

Responsibility for engineering errors depends on contract structure, but costs almost always flow back to the owner in some form.

Outcomes may include:

- Redesign fees

- Change order premiums

- Schedule extensions

- Lost productivity

- Financing and carrying costs

Even when responsibility is disputed, delays and uncertainty create real financial exposure.

Why Engineering Errors Are Often Invisible in Early Quotes

Many steel building quotes are prepared before engineering is complete. This is not inherently wrong, but it creates risk.

Lower quotes may assume:

- Simplified loads

- Generic foundations

- Minimal connection detailing

- Standard erection conditions

This is why owners frequently encounter major differences in cost when comparing proposals and discover why steel building quotes vary so widely after engineering scope becomes clearer. Higher quotes often include full engineering scope upfront. These approaches are not equivalent, even when building dimensions appear similar.

Engineering Accuracy as a Cost Control Tool

Engineering is not just a compliance requirement. It is a cost control mechanism. Across the country, structural design accountability is guided by Engineers Canada, which sets professional practice standards to protect public safety in engineering work.

Accurate engineering:

- Reduces redesign cycles

- Improves permit approval speed

- Minimizes erection complications

- Supports predictable scheduling

- Improves long-term building performance

Engineering typically represents a small percentage of total project cost, but it governs a large portion of project risk.

Final Perspective

Most steel building cost overruns attributed to construction issues originate in engineering decisions made early in the project.

Engineering errors rarely appear dramatic at first. They appear as small assumptions, deferred decisions, or incomplete scope. Over time, those decisions increase cost through redesigns, delays, and operational limitations.

In steel construction, accurate engineering costs less than correction and far less than living with the consequences of early assumptions.

Reviewed by the Tower Steel Buildings Engineering Team

This article has been reviewed by the Tower Steel Buildings Engineering Team for technical accuracy, real-world applicability, and alignment with Canadian steel building design and construction practices.

1. Who is responsible for engineering accuracy on a steel building project?

Responsibility depends on the contract structure, but engineering accuracy typically involves the steel building supplier, the structural engineer, and the foundation designer. When coordination between these parties is unclear, costs often shift to the owner through redesigns, delays, or change orders.

2. Can a steel building be code-compliant and still be poorly engineered?

Yes. A building can meet minimum code requirements and still be unsuitable for its intended use. Common examples include insufficient serviceability limits, incomplete load assumptions, or foundation coordination issues that create long-term operational problems and additional cost.

3. Why do engineering errors often appear after permits are issued?

Permits are frequently issued based on preliminary or partial information. Engineering errors surface when detailed coordination begins between steel, foundations, erection sequencing, and site conditions. At that stage, corrections are more expensive and disruptive.

4. Do engineering revisions usually affect project schedules?

Yes. Engineering revisions often trigger a chain reaction involving fabrication changes, inspection re-reviews, erection rescheduling, and coordination delays. Even small design changes can extend timelines significantly once construction has started.

5. Is it better to over-engineer a steel building to avoid problems?

Not necessarily. Over-engineering can increase material, fabrication, and foundation costs without improving performance. The goal is accurate engineering aligned with actual loads, site conditions, and building use, not excessive design or minimal compliance.

6. How can owners reduce the risk of engineering-related cost overruns?

Owners can reduce risk by ensuring engineering scope is clearly defined early, confirming coordination between steel and foundation design, reviewing erection assumptions, and avoiding quotes that defer engineering decisions until late in the project.