Engineering decisions shape the total cost of a steel building project far more than most buyers realize. While material pricing and building size receive the most attention early on, it is often the accuracy of engineering decisions that determines whether a project stays on budget or quietly accumulates unnecessary cost and risk.

Over-engineering and under-engineering are frequently discussed as technical problems, but in practice they are financial ones. Both can increase total project cost, although in very different ways. One inflates material and construction expenses. The other introduces delays, rework, inspection failures, and long-term performance exposure.

This article explains how over-engineering and under-engineering occur in steel building projects across Canada, how each affects cost, and why balanced engineering consistently delivers the best financial outcome.

What Engineering Means in a Steel Building Context

Engineering in steel building construction is not about making a structure as strong as possible. It is about designing a system that satisfies code requirements, site conditions, and functional needs without unnecessary excess.

Canadian building codes establish minimum acceptable performance, not optimal material efficiency.

Proper steel building engineering considers:

- Intended building use and occupancy

- Snow, wind, and seismic loads specific to location

- Soil conditions and foundation interaction

- Clear spans, crane loads, and equipment demands

- Long-term serviceability and maintenance

When engineering decisions drift too far in either direction, costs rise.

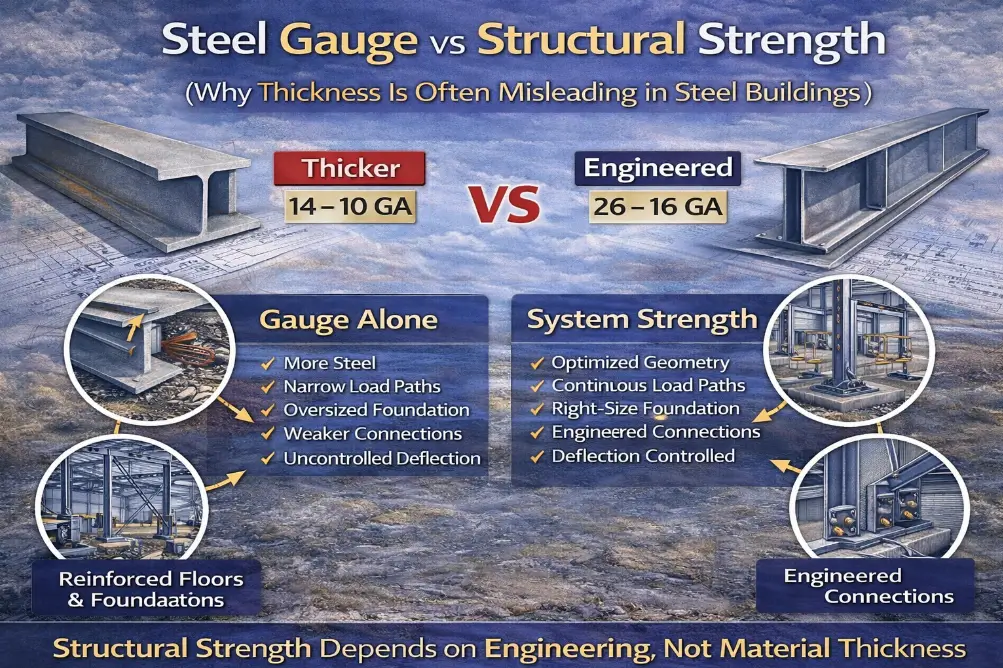

What Over-Engineering Looks Like in Practice

Over-engineering occurs when structural components are designed significantly beyond what codes, loads, and usage actually require.

Common examples include:

- Excessively heavy frames for moderate spans

- Oversized columns and rafters applied uniformly

- Reinforcement added where it provides no functional benefit

- Generic conservative designs reused without site-specific adjustment

Over-engineering often results from limited early site data, risk-avoidance habits, or a lack of coordination between engineering and fabrication teams.

To the buyer, the building may appear robust. The additional cost, however, is real and permanent.

Cost Impacts of Over-Engineering

Over-engineering increases cost in ways that are often underestimated.

Increased Material Costs

Heavier steel sections increase tonnage, which raises raw material, fabrication, transportation, and handling costs.

Longer Fabrication Timelines

Larger members require more processing, welding, and shop time, which can extend production schedules.

Higher Foundation Costs

Additional steel weight increases foundation loads, often requiring larger footings, deeper piers, or more reinforcement.

Reduced Erection Efficiency

Oversized components can require heavier lifting equipment and slow erection, increasing labour and equipment costs.

In many cases, buyers pay for capacity that will never be used.

Why Over-Engineering Is Often Mistaken for Quality

It is common for buyers to equate heavier steel with better construction quality. While understandable, this assumption is inaccurate. Buyers should confirm engineering assumptions before requesting a quote.

Quality engineering is not defined by maximum strength. It is defined by appropriateness. Canadian codes already include safety margins. Excessively exceeding those margins rarely improves performance or longevity.

A properly engineered steel building can achieve a 30 to 40 year service life when coatings, foundations, and maintenance are appropriate, without unnecessary material use.

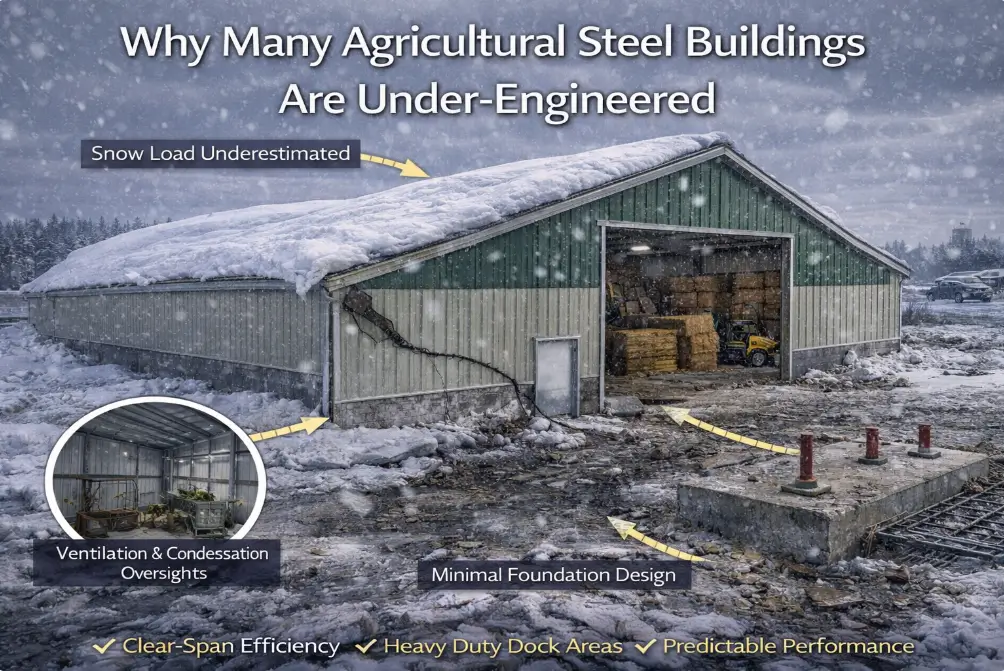

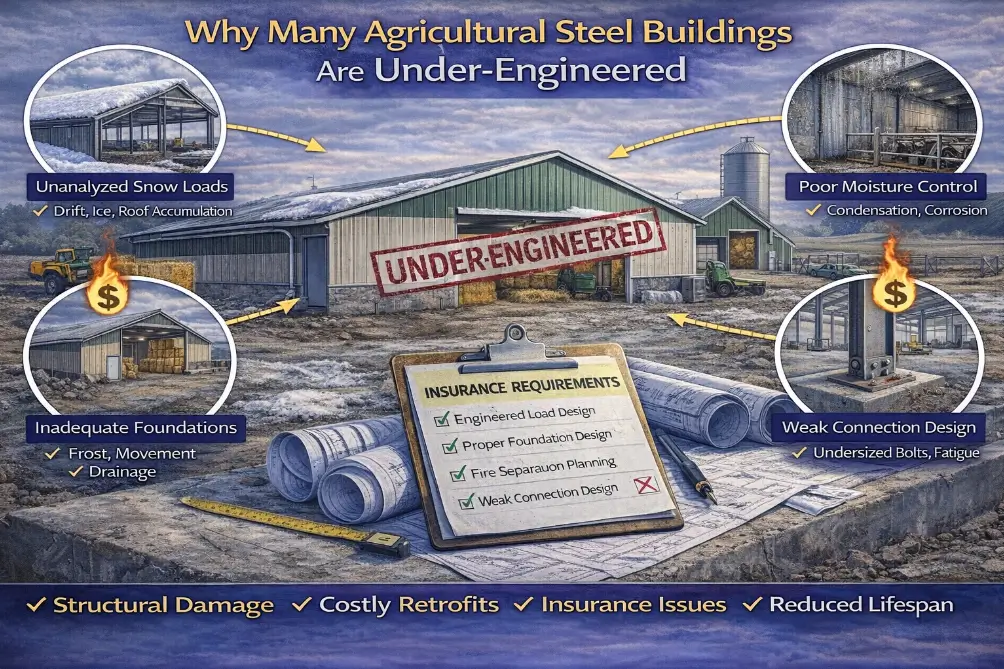

What Under-Engineering Looks Like in Practice

Under-engineering occurs when design decisions fail to fully account for real-world conditions or intended use.

Common examples include:

- Snow loads based on regional averages instead of site-specific data

- Ignoring drift zones near parapets or adjacent structures

- Underestimating crane, mezzanine, or equipment loads

- Designing foundations without adequate soil information

Under-engineering often appears economical at the quotation stage. Its consequences surface later.

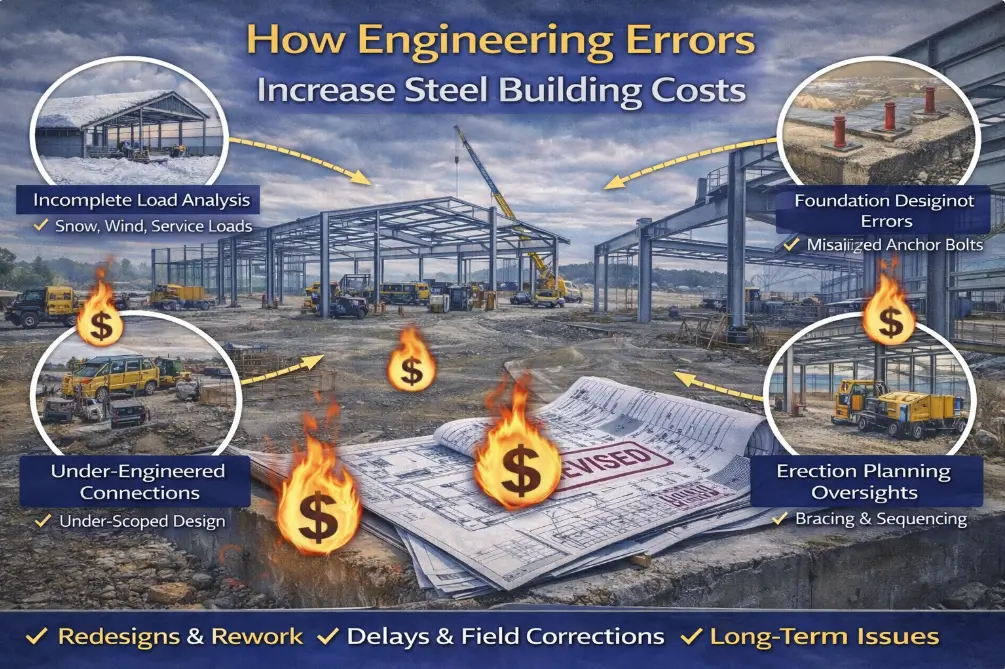

Cost Impacts of Under-Engineering

Under-engineering almost never saves money over the life of a project. Instead, it shifts costs to later stages where correction is expensive.

Failed Inspections

Inspectors may reject drawings or site conditions that do not meet code intent, delaying permits or occupancy.

Redesign and Re-Engineering

Correcting under-designed elements often requires revised calculations, new drawings, and approval cycles.

Fabrication and Erection Delays

Discovering deficiencies during fabrication or erection can halt work while solutions are developed.

Increased Insurance and Financing Scrutiny

Insurers and lenders increasingly scrutinize marginal designs, even when code compliance is technically met.

Under-engineering transfers risk from design to construction and operations, where it is far more costly to manage.

Why Under-Engineering Is Harder to Detect Early

Unlike over-engineering, under-engineering is not immediately obvious. Drawings may appear complete and steel may be fabricated without issue.

Problems typically emerge during:

- Municipal inspections

- Erection alignment checks

- Early snow, wind, or service load events

At that point, options are limited and corrective work often disrupts schedules and budgets.

The Role of Codes and Standards in Balanced Design

Canadian steel building projects are governed by national and provincial codes and standards, including CSA requirements.

These standards define minimum thresholds, not optimized solutions.

Over-engineering exceeds those thresholds unnecessarily. Under-engineering risks falling short under real conditions.

Balanced engineering works within code frameworks while tailoring design to site-specific loads, soils, and usage.

Why Balanced Engineering Produces the Lowest Total Project Cost

Balanced engineering aims for fit-for-purpose design, not minimum material or maximum strength.

Key characteristics include:

- Site-specific load analysis

- Accurate soil and foundation coordination

- Targeted reinforcement only where required

- Clear communication between engineer, fabricator, and erector

This approach reduces redesign, limits inspection issues, and keeps costs predictable.

How Buyers Can Reduce Engineering-Related Cost Risk

Buyers do not need to be engineers to protect themselves from costly design extremes. Asking informed questions early provides clarity.

Effective questions include:

- Are loads based on site-specific data or generalized assumptions?

- How were foundation loads coordinated with soil conditions?

- Are heavier sections used strategically or uniformly?

- What assumptions were made about future use or expansion?

Clear answers indicate thoughtful engineering rather than generic design.

Engineering Accuracy Protects Both Budget and Performance

Over-engineering wastes capital. Under-engineering introduces uncertainty. Engineering accuracy plays a major role in how steel building prices are calculated and defended during permitting.

Both reduce overall project efficiency.

Balanced engineering delivers code-compliant performance without unnecessary material use or downstream risk.

Final Perspective for Canadian Steel Building Buyers

Engineering decisions are among the most influential cost drivers in a steel building project. They affect material usage, foundation requirements, fabrication schedules, inspections, financing, and long-term performance.

The goal is not the strongest building possible, nor the lowest initial engineering cost. The goal is a structure engineered precisely for its site, purpose, and expected lifespan.

In steel construction, accuracy costs less than correction.

Reviewed by the Tower Steel Buildings Engineering Team

This article has been reviewed by the Tower Steel Buildings Engineering Team to confirm technical accuracy, alignment with Canadian building codes, and consistency with real-world steel building engineering, fabrication, and erection practices across Canada.

The review reflects decades of combined experience working with commercial developers, agricultural operators, industrial owners, municipal inspectors, insurers, and lenders on steel building projects nationwide.

1. What is the difference between over-engineering and under-engineering?

Over-engineering occurs when a steel building is designed with significantly more material or capacity than required by code and intended use. Under-engineering occurs when loads, site conditions, or usage demands are not fully accounted for. Both increase total project cost, but in different ways.

2. Does over-engineering make a steel building last longer?

Not necessarily. Longevity depends more on proper load design, coatings, foundations, and maintenance than on excess steel weight. Properly balanced engineering can deliver a 30 to 40 year service life without unnecessary material use.

3. Can under-engineering cause inspection failures?

Yes. Under-engineered designs often fail during plan review, foundation inspection, or erection when real-world conditions expose insufficient load capacity or incomplete assumptions.

4. Do insurers and lenders care about engineering accuracy?

Increasingly, yes. Insurers and lenders often review structural documentation and may scrutinize marginal designs even when code compliance is technically achieved. Balanced engineering reduces financing and insurance risk.

5. How can buyers tell if a steel building is over-engineered?

Buyers can ask whether structural members are sized uniformly or selectively, whether site-specific data was used, and how foundation loads were coordinated. Clear, reasoned explanations usually indicate appropriate engineering rather than excess conservatism.

6. Who is responsible for engineering accuracy in a steel building project?

Structural engineering accuracy is typically the responsibility of the steel building manufacturer’s engineering team, but it depends on complete and accurate input from the owner regarding site conditions, usage, and future plans.